Tom Emerson, 6a Architects

ArchIdea 61 Interview

August 2020

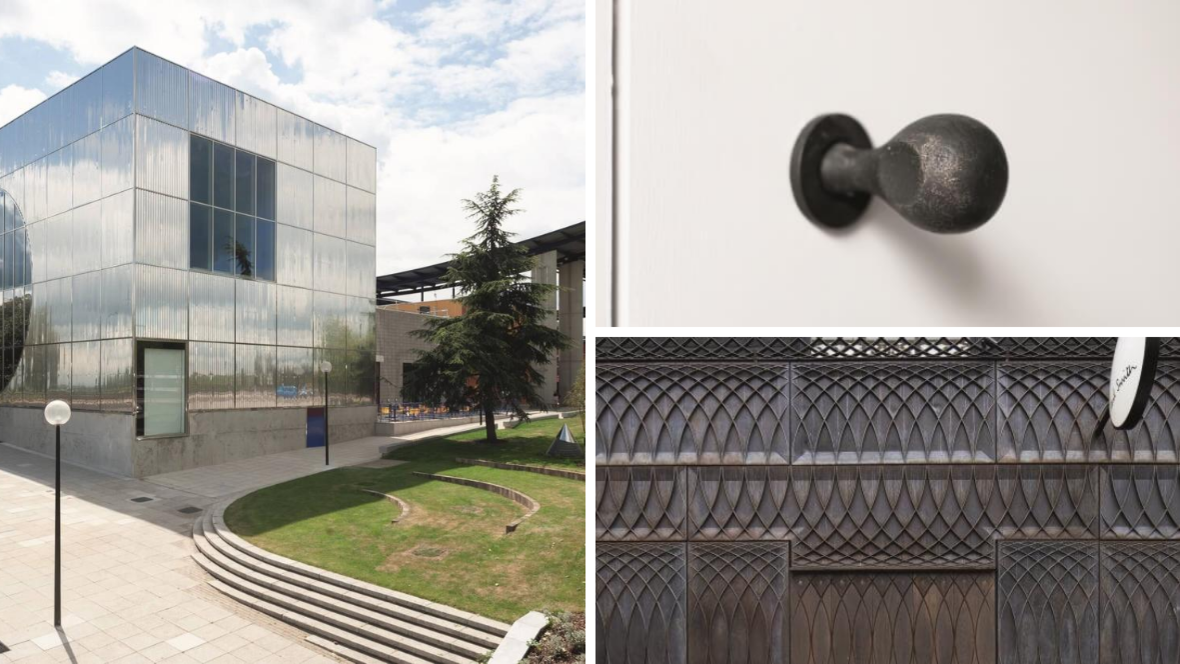

A doorknob with a thumbprint, the elegantly rounded ending of a hand railing, roof lights clad with charred wood: like other projects of the architectural office 6a Architects, based in London and led by Tom Emerson and Stephanie Macdonald, the contemporary art exhibition space Raven Row has some eye-catching details, suggestive of sentences in a poem. In times when designing is often restricted to assemblage of prefabricated elements, this special attention for details seems rebellious.

However, Tom Emerson denies that there is any intention of going against the stream or being focused on details. "In our work, detailing is a pragmatic response to the conditions we are working in", he elucidated at ETH Zürich, where he is a professor in the Department of Architecture. "Most of our earlier projects have been in London. Unlike most cities, London is formless and messy. It is a city that doesn’t accept concepts or master plans very well. Doing a project always means that you have to deal with the edges of this or the corner of that, the meeting of this and that. You cannot just design something, you need to respond to irregularity. That is even more the case when projects are about reuse and transformation, or about listed buildings."

It is not only that you respond to what is physically there, but you have an interest in stories that are connected with a building or a place.

"Yes, often there are stories that fascinate us. We discover these stories through archives, through a kind of a building archaeology. For Raven Row in the London neighbourhood of Spitalfields, we transformed two Grade 1 listed buildings. It turned out that the modern history of London had gone through these buildings. You didn’t need to go on some kind of tour, you just had to stand there and dig into the past. Originally the buildings were built by the French Huguenots, the first immigrants in that part of London. They became very wealthy in the silk trade, but went bankrupt when this trade opened up. After the Huguenots there was a wave of Jewish immigration as a result of the pogroms in Russia. Then came the Asians, followed by a demolition spree that raged through the whole district in the 1960s. Despite their ruinous state, the two buildings on Raven Row were spared and finally the art world rediscovered them. While we were making this contemporary art exhibition space, the question was how to retain something of these narratives in the materials."

You are not obliged to relate to these stories as an architect. What makes the stories relevant for you?

"Well, you have to make something that also means something. In the case of Raven Row we came across this amazing collection of archive photographs made by many anonymous photographers. The photographs mysteriously chronicled the life of these buildings over seventy-five years. Some of them showed burnt-out rooms. A Japanese colleague told us that in Japan there is a technique for cladding buildings with burned wood. One thing led to the other, and suddenly there were resonances between what had happened by accident and what happened by design. In the sixties, when the buildings were almost falling apart, the cast iron of the façade was stolen. So when we had to make a new façade, we made it in cast iron, to return the missing material. We didn’t have to do that, but for a contemporary art centre where you cannot do a great deal visually apart from creating white spaces, some of the building process, some of its materialization, recalls and brings about what you might call false traces. By false, I mean that these traces evoke something but it is not clear to everybody what they are about.

Most people will not understand why the roof lights at Raven Row have been clad with charred wood. For them it is just a form, a texture, a colour. However, for us, as the architects, these stories help us to make certain choices and to have a kind of discipline in design."

Raven Row: Images by 6a Architects

Raven Row: Images by 6a Architects

How did you become interested in stories as a starting point for designing?

"When Stephanie and I studied architecture, we were very much influenced by Richard Wentworth, a British artist who is famous for a photography project that goes back to the seventies. Basically this project is about reading the city: how the city is made, how it breaks, how it is repaired. What kind of processes are at work, and how they reveal a culture’s metabolism. At the same time I was writing my dissertation about the French writer George Perec. His literature is about convoluted stories, stories within stories, bifurcations and literature as a game. So yes, there has been affinity with stories from the very start of our practice. When you permit yourself a closer look at places, they start to reveal stories. These stories are always present in the material you are looking at, but you have to discover them yourself.

Image: David Grandorge

For instance, there were photographs of the room at Raven Row that was burnt. I found out that, before it burned, that there was in the corner a stack of about twenty paraffin lamps. A year later, the room burned. It is plausible that the fire was caused by these paraffin lamps. Then I found out that the fire had taken place when the building beside it was under construction. Perhaps the paraffin lamps belonged to the construction company and were stored there. Creating these stories is a bit like playing detective."

Stories are ephemeral, in contrast with the solidity and permanency of architecture. Can you tell me in what way stories contribute to your architecture?

"We are very much interested in the materialization of stories, in how materials and processes are essentially the record of a culture. And we, as architects, are in the business of materializing things. That is what you do when you make buildings – they are made of stuff. For example, our studio is an ongoing project. Some years ago we had a little building on the patio, and then rebuilt it to link the two other buildings into one. While doing so, we discovered the whole of London in this yard of three metres wide and six metres long. There were bits of ceramics, oyster shells, cast iron pipework, brickwork, concrete and timber. I am sure that if you were to cut a little pocket like this out of Barcelona or New York, it would produce a different materiality."

Image: David Grandorge

One could say architecture often has the pretension of being an ultimate aesthetics, an ultimate vision, that could be meaningful over time. The architecture of 6a architects seems to be very different in this respect.

"I agree. When we do a building, it is neither the beginning nor the end. It is just a period in the life of a place. We inherit it, and then we pass it on, and somebody else will do something to it. It is a realistic attitude, which ties in with another preoccupation that we have: the landscape and the garden.

Nature helps us to understand the building as something that is built and then decays, and then is rebuilt and decays again. It is a metabolism which isn’t that dissimilar to everything else within nature."

Do you aim to show this metabolism in your architecture?

"To try to avoid it, as happens often in architecture, is to deny a basic condition of the world and being alive, and to try pretending you don’t age. It can be considered a criticism of a certain kind of modernism, that arrives immaculate and stays immaculate. In my view this is not the case because a building appears necessarily already imperfect. It is not that we strive for imperfection, but we acknowledge that imperfection is always there, from the very beginning."

That could also be called a very modern approach.

"Contemporary yes, modern no. Or at least not modern with a capital M. I associate the word modern with a certain kind of twentieth century thinking. There is no claim to truth in what we design. It is almost anti-conceptual. There are a lot of judgements, but we never use a single concept."

Although the work of 6a architects is not primarily about details, they play a significant role in your projects. How do you manage to get them built?

"Raven Row was partly a new building and partly a restoration. So we had to work with experts in restoration. Once you get into that world, you realize that there are plaster makers and iron foundries and carpenters, all those specialists who serve the heritage industry and have incredible skills. They are rarely employed in the contemporary building industry. But they are there, and they are literally very close. It is not difficult to find them. The cast iron of the façade of the Paul Smith shop in London was done in a foundry in Essex, where they also make the edges of steps in the Underground. That was small fry for them, but they were really great. I have a strong admiration for that kind of craftsmanship."

Image: David Grandorge

Could the use of old fashioned craftsmanship also be considered a commentary on contemporary building practice?

"I don’t like the word commentary. I would rather say we like to be responsive to what is already there, because we are not always using this craftsmanship - it depends on the situation. For the gallery in Milton Keynes, the building material is in essence industrial and cheap. But it is in my mind not different from the other projects. The way decisions were made and the way the building material related to the place, were similar. Milton Keynes is a new town, emerging out of the Welfare State. The budget for the gallery was very tight and demanded cheap shed stuff. Or, to give another example: for the Paul Smith shop, we were looking at what Paul Smith does in fashion. In our interpretation, he is to fashion what cast iron is to London. London is brick and the second material is cast iron. Paul Smith is essentially a tailor. As a tailor he makes suits, but as a fashion designer he changes a button, he cuts something, he makes adjustments. Therefore we proposed to him an analogy to these adjustments: cast iron. The interlocking circles were borrowed from balustrades of balconies."

Some specifically designed details, like the doorknob with a thumbprint and the rounded end of the hand railing in Raven Row, generate a feeling of melancholy, as if they testified to something that is not there any more. Is that on purpose?

"Those two details have hung around with us way longer than we ever expected. When we did the doorknob with the thumbprint, we were literally just doing the doorknob. We had a clay model, and it was fun to press into it. After it was cast in sand, it came out with a great texture. There is a tactile quality to it, even though visually it is quite subtle. It didn’t have a greater degree of intention than in other decisions. But it seems to be better remembered than other parts, maybe because of the slightly melancholic character it has. You cannot design for that. You can design spaces, material, structure, but you cannot design how people respond to it. What you can do is to try and make spaces that are engaging and, like literature, have different narrative structures."

Milton Keynes Gallery, image 6a Architects

Paul Smith London, image David Grandorge

Want to read more interviews like this? ArchIdea is our bi-annual magazine that features well known and upcoming architects from all over the world alongside some of the latest projects in which our floor covering has been installed.

To start receiving your FREE copy, sign up here